Tokyo is starting to feel that familiar tingle that hits a city just before a global sports carnival. In a little over two months—13 to 21 September, to be exact—the World Athletics Championships will return to the National Stadium, luring roughly 2,000 competitors from more than 200 countries for nine days of gloriously frantic track and field action. It will be only the second time the Japanese capital has staged the meet, the first being in 1991 when Carl Lewis and Mike Powell rewrote the long-jump record book.

On the surface the build-up feels smooth, almost business-like. Governor Yuriko Koike certainly projects that vibe. “With just four months to go, excitement in Tokyo is growing by the day,” she told reporters on Kids’ Athletics Day in early May. “We will further accelerate preparations in close cooperation with the Local Organising Committee.”

World Athletics president Sebastian Coe, standing alongside Koike in the Tokyo Metropolitan Government building that morning, matched her optimism. “Through regular updates and on-site visits, I am pleased to see that preparations are progressing smoothly,” he said, flashing the sort of grin only a two-time Olympic champion can pull off.

Yet dig beneath the calm exterior and you find a city trying to outdo its own Olympic legacy. The National Stadium’s LED façade has been repurposed to bathe the venue in Edo Purple—the official colour of the championships—while officials have quietly rejigged timetables so that every one of the 14 stadium sessions lands in a prime-time TV window for North America, Europe and, of course, Japan’s late-night sports die-hards.

And then there’s the sustainability drive, which feels more like a crusade than a box-ticking exercise. In June, Osaka-based Revo International was unveiled as an official event supplier, tasked with turning mountains of Japan’s used cooking oil into bio-based Sustainable Aviation Fuel. “We are deeply honoured to contribute… by supplying biofuel to this global sporting event,” company president Tetsuya Koshikawa said, linking the initiative to Tokyo’s “circular, resource-efficient society” goals. Event chair Mitsugi Ogata went further: “With the mission of setting a ‘Tokyo Model’ for future competitions, together we will realise a world-class sustainable event.”

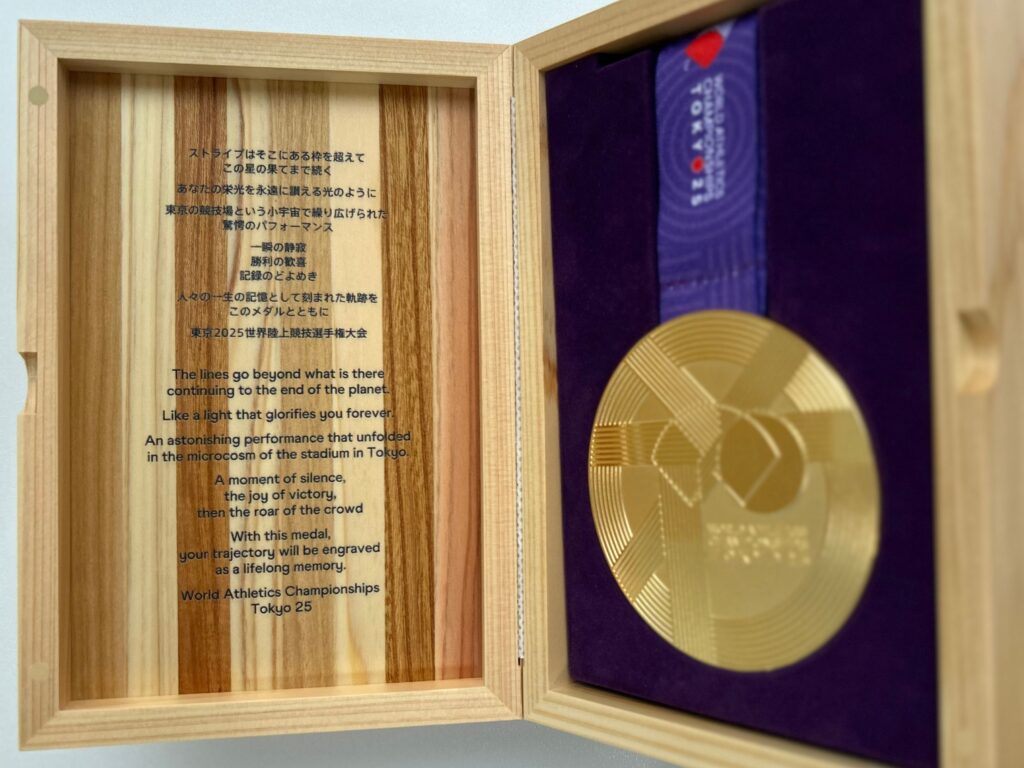

Ogata’s passion for symbolism spilled into the championship’s newly unveiled medals. At the 100-days-to-go mark in early June he brandished the gold, silver and bronze designs—each presented in a case carved from locally sourced Tama wood. “The medal case reflects our commitment to sustainability,” he noted, insisting the shimmering discs “become a powerful source of motivation for athletes… and a lasting memory for fans.”

Athletes, for their part, are already cranking up the competitive rhetoric. Britain’s Neil Gourley, silver-medallist at March’s World Indoors in Nanjing, has Jakob Ingebrigtsen squarely in his sights in the 1500 metres. “It sounds like my turn, doesn’t it? I’m certainly going with that ambition,” the Scot joked to the BBC, conceding that dethroning the Norwegian prodigy will be “incredibly challenging” but vowing to “take my turn on the top of the podium” in Tokyo.

Meanwhile, the Local Organising Committee is leaning into grassroots fever. Volunteer training sessions now double as tourism masterclasses—guides learn how to steer visiting fans toward ramen joints tucked down Shibuya shortcuts—while high-school art students are sketching “Every Second, Sugoi!” murals destined for metro stations. Pragmatics matter too: an extra tranche of affordable seats was released last week after initial sales blew past expectations, and transport officials promise that the newly extended Yamanote Line service will mean “no one should miss a final because of a train queue,” as one official quipped off-mic.

For all the fanfare, there remains the unspoken reality that Tokyo is still chasing its own Olympic ghosts. Empty seats and pandemic protocols dogged the 2020 Games, and officials know these championships are their mulligan—a second swing at showing the world how Japan hosts sport when its grandstands are actually full.

Coe, for one, appears convinced. “I am more determined than ever to ensure that WCH Tokyo 25 becomes one of the year’s most significant sporting events, engaging younger generations in the process,” he said before ducking into yet another planning meeting.

If the current mood holds, he may get his wish. Tokyo is humming again, the kind of hum that hints at just-finished track spikes and last-minute visa confirmations. And in a city that has rebuilt itself more times than most metropolises have changed their subway maps, that hum usually means one thing: the show is about to start.