Japanese scientists have taken a dramatic step toward rewriting the outlook for Parkinson’s disease (PD). In a Phase I/II clinical study at Kyoto University Hospital, surgeons implanted dopamine-producing neurons grown from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into the brains of six people living with mid-stage PD. Twelve months on, four participants show measurable motor improvement and none have experienced serious adverse events—an unprecedented milestone for regenerative neurology.

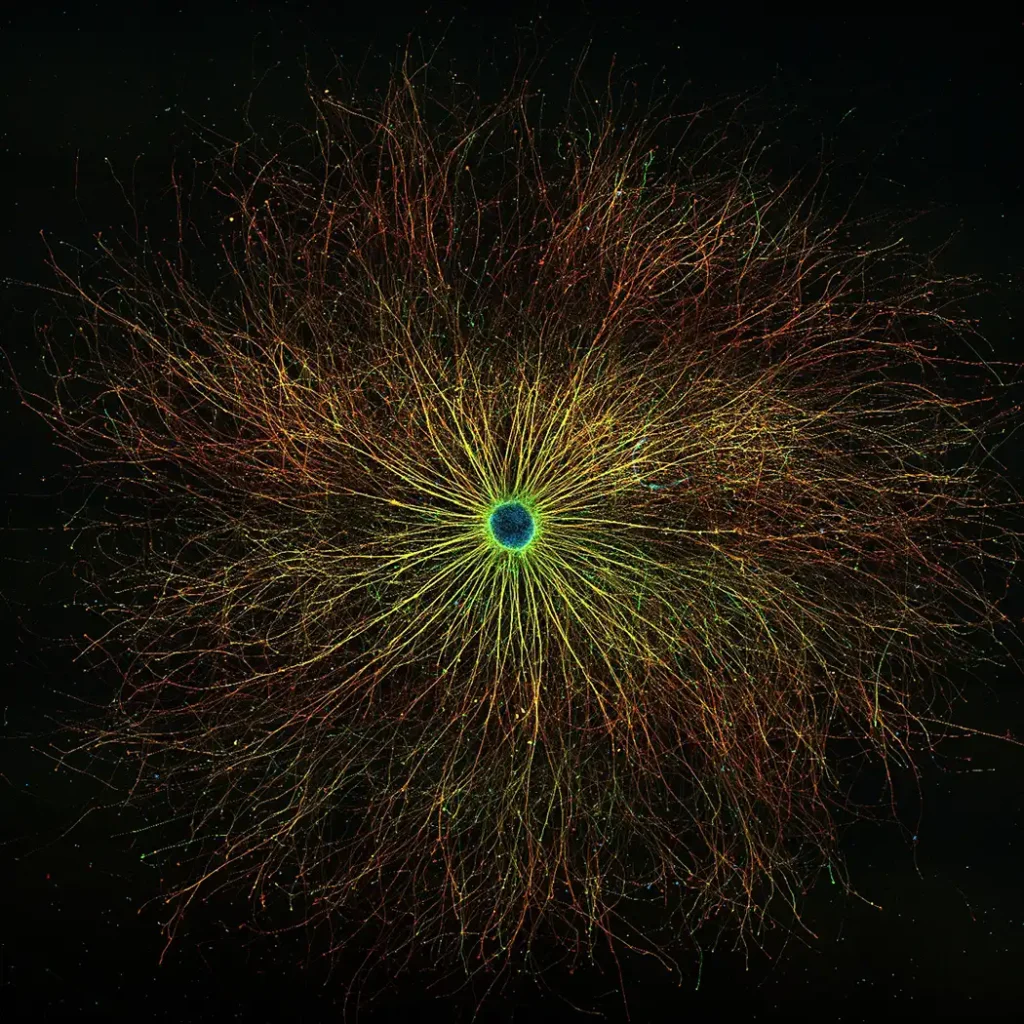

Researchers at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) first reprogrammed donated skin cells into iPSCs, then coaxed them to become midbrain dopaminergic progenitors—the very cells that degenerate in Parkinson’s. Roughly 2–3 million of these progenitors were injected into each patient’s putamen, the brain’s dopamine hub. Post-operative imaging confirmed that the grafts survived and began releasing dopamine, the neurotransmitter that calms tremors and smooths movement.

Motor scores on the “off-medication” Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale improved by up to 30 percent in responders, and no tumor formation or immune rejection was detected—thanks in part to careful HLA matching of the donor cells. “It’s the strongest signal yet that iPSC-derived neurons can integrate and function in the human brain,” lead neurosurgeon Professor Jun Takahashi told reporters, while emphasising that larger, longer trials are essential.

Parkinson’s affects more than 8.5 million people worldwide and is the fastest-growing neurological disorder, according to the World Health Organization. Current drugs only ease symptoms; they cannot halt or reverse the underlying neuron loss. A reliable stem-cell therapy would instead replace those lost cells, potentially offering long-term relief or even disease modification.

The Kyoto team plans to expand enrollment to 30 patients and follow participants for at least three years to monitor durability and safety. Parallel trials in Sweden, the United States and China are already gearing up, setting the stage for an international race to turn stem-cell grafting into a mainstream therapy. Scientists caution that challenges remain—scaling production, ensuring long-term graft survival, and proving superiority over existing deep-brain-stimulation and drug regimens.